what resources are needed to develop improvement capability in hospitals

- Research commodity

- Open up Admission

- Published:

How to sustainably build chapters in quality improvement within a healthcare system: a deep-swoop, focused qualitative analysis

BMC Health Services Inquiry volume 21, Article number:588 (2021) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

A key feature of healthcare systems that deliver high quality and toll performance in a sustainable way is a systematic approach to chapters and capability edifice for quality improvement. The aim of this inquiry was to explore the factors that lead to successful implementation of a program of quality improvement projects and a chapters and capability edifice programme that facilitates or support these.

Methods

Between July 2018 and Feb 2020, the Southern Adelaide Local Health Network (SALHN), a network of health services in Adelaide, Due south Australia, conducted three capability-oriented capacity building programs that incorporated 82 longstanding individual quality improvement projects. Qualitative analysis of information collected from interviews of xix projection participants and 4 SALHN Comeback Kinesthesia members and ethnographic observations of 7 projection squad meetings were conducted.

Results

We institute iv interacting components that lead to successful implementation of quality comeback projects and the overall program that facilitates or support these: an agreed and robust quality improvement methodology, a skilled faculty to assistance improvement teams, active involvement of leadership and direction, and a deep agreement that teams matter. A strong condom culture is not necessarily a pre-requisite for quality improvement gains to exist made; indeed, undertaking quality comeback activities tin contribute to an improved safety culture. For most projection participants in the program, the fourth dimension commitment for projects was significant and, at times, maintaining momentum was a challenge.

Conclusions

Healthcare systems that wish to deliver loftier quality and price performance in a sustainable fashion should consider embedding the iv identified components into their quality comeback chapters and capability building strategy.

Background

Given the burden imposed on health systems by ageing populations, technological changes, and more recently the COVID-19 pandemic, delivering high quality healthcare in a cost-effective way remains a claiming [i]. A key feature of healthcare systems that evangelize high quality and price performance in a sustainable way is a systematic approach to capacity and adequacy building for quality comeback [2,3,4,5].

Quality comeback (QI) can be defined every bit: securing agreement of the circuitous healthcare environment; applying a systematic approach to problem solving; designing, testing, and implementing changes using existent-fourth dimension measurement for improvement; and making a difference to patients by improving safety, effectiveness and feel of care [vi]. QI capacity and capability edifice leverages the inherent self-sustaining ability of organisations and systems to recognise, analyse and improve quality problems by controlling and allocating available resources more than finer [2]. Organisations can use these resources to back up the commitment of their core strategic priorities, such as improving care pathways, continuously improving, and enhancing access to services by patients [3]. If capacity and adequacy building in QI is indeed a pre-requisite for high performance health systems, what are its features when undertaken sustainably and continuously over a flow of years?

QI, and associated chapters and adequacy building, is at present a oft used method to attempt to better wellness systems in high, medium and low income countries [7,8,ix]. However, fidelity of QI methods is often variable and projects may be led by professionals who lack the expertise or resources to instigate the changes required [7]. Scientific approaches for scale-up of programs that amend healthcare systems [viii, 9] have been developed, but at that place has been bereft attention to sharing the lessons of successes and failures [7, eight]. Therefore, given the considerable resources spent on QI, agreement the features of sustainable QI programs that are generalisable to other organisations is of import.

An atypical instance of a long-term capacity and capability building program for QI is at the Southern Adelaide Local Health Network (SALHN), in South Australia, Australia. SALHN'southward Department of Surgery and Perioperative Medicine has a 15-year history of implementing and sustaining QI projects via an internally developed capability and support program known locally every bit the Continuous Comeback Programme (CIP). What is unusual, although by no means unique [v], is the length of time (fifteen years) that the CIP has been in identify. This ways that the CIP has had time to evolve and foster a continuous support infrastructure, experienced personnel, and corporate memory.

Southern Adelaide Local Health Network (SALHN)

SALHN is a network of health services in the southern suburbs of Adelaide, South Australia. SALHN comprises a major tertiary and instruction hospital (Flinders Medical Centre), a regional customs infirmary (Noarlunga Hospital), mental health services, sub-astute services, and principal intendance clinics. SALHN manages around 700 acute infirmary beds.

The Continuous Improvement Programme (CIP)

The Department of Surgery and Perioperative Medicine initially used methods derived from Intermountain Healthcare in Utah, USA, adult primarily by Dr. Brent James [10, 11]. Notwithstanding, over time other evidence-based methods such equally Lean [12] and the Model for Improvement [thirteen] were integrated to provide a toolkit of QI techniques. CIP too incorporated principles from SALHN's Redesigning Care Unit of measurement which used process redesign and lean thinking to improve patient flow across the organisation [fourteen]. SALHN have developed an viii-pace process (Define the Trouble, Breakdown the Trouble, Gear up a Target/Mission Statement, Cause Analysis, Interventions, Implementation, Evaluate/Assess Impact, and Continuous Improvement – Table 1) to organise the toolkit of QI techniques and to be their overarching QI structured methodology (SALHN Continuous Comeback Framework) [15]. The Surgical Department established an Improvement Faculty to bus, mentor, and train staff, and to progressively improve their methods. Essentially, over a decade and a half, the CIP went from discrete and bolted-on projects to a coherent, coordinated program of piece of work.

CIP was initially implemented in surgical contexts at SALHN in 2004. SALHN executive then supported the expansion of CIP in 2018 from the Surgical Department into a SALHN-wide plan, across all services.

The aims of SALHN CIP are at organisation level – to build capability as a high performing health service and develop a collaborative continuous improvement culture; and at a participant level - to learn a standard approach to continuous comeback and problem solving which is applicable beyond all levels of staff, to help the organisation create reliable systems and provide safe, loftier quality care. CIP is designed to provide an opportunity for participants to acquire how to identify and solve problems in the workplace they are passionate about, partner to work within a squad, and utilise improvement methodology to step through the trouble systematically.

The CIP'south instruction component commences with introductory 3½ solar day off-site training sessions with presentations by both senior staff from SALHN and members of the Improvement Faculty. The initial topics covered include an overview of the CIP's history, an outline of its key objectives, the development of QI and the demand for a systematic improvement framework. Days 2 and 3 involve small group work, with an introduction to the diagnostic tools used in the CIP, such as breaking down the trouble, process mapping, brainstorming, multi-voting and Pareto charts, organised by the SALHN Continuous Improvement Framework [15, 16]. The importance of measurement and the significance of human factors science to QI are stressed in Comeback Faculty presentations. Presentations on 24-hour interval four include standardisation in clinical exercise and the significance of reducing, where possible and desirable, unnecessary variation in healthcare. The sessions likewise provide opportunities for groups to work through practical cases using CIP methodologies.

Subsequently the introductory 3½ day off-site training sessions, participants then select QI projects to work on and atomic number 82. The QI projects are based on improving clinical problems e.chiliad., related to patient safe, length of stay, or patient experience – see Additional file 1: Details of CIP projects for examples. The participants invite clinicians (doctors, nurses, allied wellness of all levels of expertise) and authoritative staff who are likely to empathise the reasons why a clinical problem exists, onto a QI project squad to collectively address the problem. They may be identified inside or across clinical departments depending on the scope and type of clinical problem or pathway that they are attempting to improve. More than i participant from the CIP may exist on a project squad.

Some 3 months after the introductory training sessions, the CIP participants attend a follow-up, full-day symposium, where each squad presents on the progress of their project. The symposium is relatively breezy and interactive, with an accent on allowing participants to learn from the experience of others.

Later on a further 3 months, participants in the CIP graduate. In this final i-twenty-four hour period session, participants need to have demonstrated that they take used CIP methods to initiate a service improvement. The project does not demand to be completed; however, pregnant progress must be presented. Minimum requirements are prepare for graduating participants, including the identification of a problem worth solving and evidence to justify the projection, brainstorming the contributing factors to the problem, creating a cause and effect diagram, identification of outcome measures and how they are to be used, and the application of a run chart.

Betwixt July 2018 and February 2020, SALHN conducted three Continuous Improvement Programs (CIP1, CIP2, CIP3) roofing 82 individual projects. Additional file 1 provides details of all projects. A summary of participant numbers in the three Programs is shown below in Additional file 1.

The Improvement Faculty

The SALHN'south Comeback Kinesthesia comprised six members at the offset of the CIP1. Kinesthesia members were initially nurses from the Department of Surgery and Perioperative Medicine who had many years of experience in undertaking QI projects. From CIP1 and ongoing, the Faculty traini and mentor other clinicians from other departments in SALHN who participate in CIP to join the Faculty. SALHN's Improvement Kinesthesia and associated researchers were interested in agreement the principles and components of the CIP and the improvement projects themselves that were generalisable to other organisations and programs attempting to undertake sustainable QI in healthcare. As well fiddling enquiry focuses on this meso-level chapters – generally, studies are of a specific project (infection command or use of radiology in the clinical microsystem [17, 18]) or organization wide studies [19,20,21]. The aim of this research was to explore the facilitators and barriers to implementing the CIP QI projects and the influence of the scaled CIP capacity and capability building program on the success of these QI projects (Tabular array ii).

Methods

Study methods

By way of executing a deep-dive study of the CIP, interviews of CIP project participants and the Comeback Faculty and observations of project meetings were conducted. Qualitative thematic analysis of information collected from these sources was conducted. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist is shown in Additional file 2.

Data collection and participants

Interviews

Staff who participated in CIP and the Improvement Faculty were interviewed for the research. The researchers briefly presented to all three introductory CIP sessions to let participants know that the research was beingness undertaken and that they may be contacted with a request for interview. The researchers purposively selected 20 CIP participants from a range of departments across SALHN to capture a range of experience and wellness services professions. The researchers anticipated reaching saturation at around 12–15 interviews, even so, as it was felt important for a range of departments to be represented, 20 CIP participants were therefore invited. Viii participants were selected from both CIP1 and CIP2 and four from CIP3 and invited to be interviewed.

There were twenty-three participants (due north = 16, lxx% females) who agreed to participate in the report comprising xix single interviews (CIP1 (n = 8), CIP2 (n = eight) and CIP3 (n = 3)) and i group interview of iv Improvement Faculty members. Of the 19 clinicians, there were ten nurses, 7 doctors, one pharmacist, and one physiotherapist. Interviews were conducted between September and November 2019 by PH and MB, who are male and accept all-encompassing feel in qualitative research (see Additional File 2, COREQ questions 2 and 5 for more details). The researchers had no formal pre-existing human relationship with written report participants (see Additional File 2, COREQ questions 6–viii for more details). Participants were approached to participate past e-mail. Interviews were conducted onsite at SALHN, and in that location was no-one else present.

The aim of the interviews was to identify, from this experienced, hands-on cohort, the barriers and facilitators to implementing QI projects that have been supported past a sustained and scaled capacity and capability support program and place how the CIP facilitated the success of the projects. Interviews were semi-structured and comprised approximately 25–30 questions depending on responses (meet Additional file iii for the schedule of interview questions). Each single interview took between thirty and 45 min, whilst the group interview took effectually 60 min. Following the earlier CIP1 and 2 interviews, questions with CIP iii participants were slightly modified to farther explore bug that had emerged. All interviews were recorded with permission and transcribed.

Observation of project teams

To gain a deeper understanding of the mechanics, interpersonal interactions, experiences, norms of the teams, and barriers and facilitators to projects, researchers (MB and PH) attended team meetings of individual projects. Researchers PH and MB attended vii meetings of four CIP project teams. Project squad members could be CIP participants or not – details are shown in Additional file four. The number of attendees at each meeting ranged from 5 to 10 (mean 8), with nearly two-thirds (due north = 36/56, 54%) of attendees being female. The mean meeting elapsing was effectually 70 min (range 0.5 to 3 h).

During the observation, the researchers took an ethnographic approach, observing how work was done, including the behaviours, interactions, and communication between the team members [25]. In addition, to guide the process, a template was developed from a meeting ascertainment guide originally produced by NHS England [26]. The template included sections on QI principles, team behaviour, and meetings standards (see Boosted file 5). Notes were likewise taken during observations and written upwardly equally soon as possible to avoid recall bias.

Given the sensitive nature of the research, it was fabricated clear to the project teams that all information would be treated confidentially and dealt with in a considerate manner. Project teams were too fabricated enlightened that findings were to be published in ways so equally to non place individual participants.

Data analysis

Interview transcripts and notes from observations were inductively and thematically analysed independently and iteratively past ii researchers, who then compared themes. Braun and Clarke's Framework for thematic analysis was used as the guiding framework [27]. nVivo v.12 (QSR International Pty. Ltd.) was used equally the assay tool. The interviews and the observations of the team meetings were analysed using the same ready of codes developed in nVivo. Project team observations were likewise deductively analysed separately using the categories from the NHS England template [26]. Information saturation was reached. Supporting quotes for each theme were extracted from the transcripts and presented with the results.

Ideals

Requisite ethics and governance approvals were obtained earlier research commenced – SALHN Man Research and Ethics Commission: HREC/eighteen/SAC/369 and Office for Research: SSA/19/SAC/162.

Results

There were 4 themes identified from the assay of factors that pb to successful historical implementation of CIP projects and the overall Program that facilitates or support these: an agreed and robust QI system, a skilled faculty to assist improvement teams, active involvement of leadership and direction, and an agreement that teams matter. These are explored in plough, together with another theme from the interviews, the human relationship between safety culture and QI, which is then followed by barriers to successful improvement projects. Shorter quotes are displayed in italics in text and longer quotes are presented in Table 3.

An agreed and robust quality improvement methodology

Interviewees appreciated the structured arroyo to the QI process, which they found benign to problem solving and decision-making. They valued being given a step-by-pace approach to problem solving (using the structure of the SALHN Continuous Improvement Framework [fifteen]), specially in a healthcare organization that is characteristically complex and high-pressured (Table two, Quote 1). Many interviewees peculiarly valued the principles of establishing the root causes of a problem rather than the rush to find a solution (Quote two).

A number of interviewees expressed an appreciation of the CIP's strong process orientated methodology. 1 doctor expressed her surprise at the value of this approach, which was so alien to her grounding in scientific methods, such as the use of randomised controlled trials. She establish the whole concept of looking at interventions in the Programme Do Written report Deed (PDSA) cycle and the apply of different kinds of outcome measures very challenging. Several interviewees mentioned the brainstorming sessions (Quote 3). I interviewee enjoyed her exposure to the PDSA wheel, "learning about that and how I can use that to my everyday exercise" (Interview no.3, nurse), whilst another, who was initially sceptical, said that she enjoyed the voting process. Another expressed a similar view, saying that they approached the training with some "feet and trepidation" (Interview no.12, physician).

The applicability of the methodology to a variety of situations (that extended exterior of the QI environs) was possibly an unexpected benefit of the grooming to some participants. Related to this, was the notion of having an agreed methodology, which results in people having a common understanding and language (Quote 4).

Several interviewees mentioned being attracted to the underlying robust methodology due to the positive impact that undertaking the CIP would have ultimately have on patient outcomes (Quotes five and 6). Some expressed the view that they would recommend the CIP because of the different simply valuable skills that it brought to patient intendance and to their own skill set (Quotes 7 and eight).

The theme of having an agreed and robust QI arrangement was again noted in the observations of the meetings. In all instances, the projection teams had clear evidence of what they hoped to achieve from their improvement project with clearly defined objectives and timeframes. All projects were focussed on resolving problems that had a significant impact on their health service.

During observations, project teams demonstrated the use of robust diagnostic tools, using established tools such as procedure mapping, cause and effect analysis and Pareto charts. An observation of a team leader respectfully asking a staff fellow member to avert rushing to solutions was noted. Extensive use of other data was besides noted, including client surveys and complaint reports, and the conclusion of patient need and clinician fourth dimension through the interrogation of patient authoritative and coding systems.

Teams were observed spending considerable time reviewing and discussing data, a process viewed as central to their QI activities. Data were ofttimes presented in handouts provided in advance of the meetings. Examples of data reviewed in meetings included weekly patient demand, yearly comparisons of patient activity, listing of patient delays in treatment, and a time- and-move study on tasks undertaken by clinicians. Whiteboards were frequently used in meetings, particularly during process mapping and voting exercises. One team participant, a long-term staff member, strongly supported the process by stating words to the effect of "nosotros have tried things in the by, just never evaluated information technology. The difference this time is the review of data".

There was much give-and-take most how to "read" the data and interpret information technology. The managers who led the meetings stressed that information should be viewed every bit a tool for improving the delivery of healthcare, not for performance management purposes. Furthermore, information technology was highlighted that people should acknowledge data around capacity and patient demand could exist confronting and that intendance should be taken not to focus on individual performance, just instead consider the organisation.

A skilled faculty to aid improvement teams

Nearly all of those interviewed considered that the Improvement Faculty, which provided preparation, mentorship and ongoing back up to projection teams, were critical facilitators to their success. Many expressed gratitude at the willingness of the Faculty to help solve problems as they arose, giving guidance to project teams on QI methodology and offering applied advice when issues were encountered (Quotes 9–10). A pre-requisite to engaging projection teams was that the grooming needed to be high quality and enjoyable (Quote iv).

Other skill sets mentioned were having a clinical lead who was "well informed near the process and the project and the methodology" (Interview no.16, nurse) and "a clinical lead – an improvement coach – I think is a must" (Interview no.eight, nurse) and support with information collection (Quotes 11 and 12). Others mentioned the need for sufficient time to tackle the problem, funding requirements, and preparation cloth and resource.

Several interviewees felt that the Improvement Faculty's job was assisted by people who had previously undertaken the CIP and had a greater understanding of QI and its applied application. The fact that more than and more people across SALHN were at present "talking the CIP linguistic communication" was seen as a significant development (Quote xiii).

Active involvement of leadership and management

Well-nigh all interviewees recognised the importance of the supportive office played by senior management, which included both hospital executive and heads of department. Their role was deemed to be a positive influence, although the nature of their support differed. For example, the Chief Executive Officer at SALHN was noted to be a key commuter of the Program, both in directing the wellness network'southward strategy to encompass it, and in her active participation in grooming sessions (Quote xiv). The CEO'south "leading from the top" was a unremarkably expressed view of her support for the Program and her delivery to have the whole organisation trained in the QI methodology and influencing other executives was crucial for buy-in from QI teams (Quote xv). Other senior executives were also seen as being supportive of the CIP past undertaking the training and involvement in projects every bit sponsors (Quote 16). In that location was likewise significant utility in the fact that senior management prioritised the CIP as an of import initiative (Quotes 16 and 17).

It was commented that senior management were in a unique position to see the bigger picture show of activities inside their health network, and because of this, were able to assist with projects that were of significance to the organisation. Conversely, feeding upwards information from the "grassroots" level gave senior direction insight into problems of which they may have otherwise been unaware. On the other mitt, one interviewee highlighted that senior management maybe underestimated the time delivery of staff undertaking the CIP and allowances need to be fabricated for this (Quote 18).

Many heads of Department demonstrated their support for the CIP in applied means, for example, by allowing time off for their staff to attend training sessions and team meetings. In some instances, they also participated in the CIP themselves with some taking railroad vehicle of detail projects. One senior medical clinician expressed the view that without the back up of her Departmental Director, the project in which she was involved would non have proceeded (Quote 19).

The influence of the senior leaders was observed in one of the project meetings. The meeting leader referred to CIP and stated that "this approach is going to be the norm" indicating that senior staff were strongly and sustainably supporting the approach.

An understanding that teams matter

The feel of working in a team to solve a trouble was considered 1 of the most enjoyable aspects of the CIP by virtually all interviewees. A number of people mentioned the camaraderie that developed amongst team members, with many likewise highlighting the benefit of forming relationships with staff that usually they would not encounter in the workplace. Of particular do good were the various perspectives that different disciplines brought (Quotes xx and 21). The fact that tangible outcomes were achieved and shared between squad members reinforced the value of the projects and contributed to a commonage sense of achievement (Quotes 22 and 23). One interviewee commented on the revelation that different professions shared the same challenges (Quote 24).

During "brainstorming" sessions, information technology was observed that some participants initially showed a tendency to consider the issues being discussed solely from their personal perspective. As the nature of the problem being discussed emerged, information technology appeared that participants became more willing to consider the views of others. An example of this related to a discussion about waiting lists, with medical staff proverb that they better appreciated the stressful impact that waiting lists also had on authoritative staff.

Obtaining the right mix of skills in the team was likewise seen every bit crucial in conducting a QI project (Quote 25). One interviewee mentioned the do good that could be gained from sourcing expertise external to the organization, such as general practitioners who co-manage patients (Quote 26). A senior doctor stressed the importance of selecting the right people to attend the commencement brainstorming session, an action that she considered could "make or break" the project.

The attitude required inside the team was to take an "open up-minded" approach to problem solving and a willingness to openly hash out options and possible solutions were seen as cardinal facilitators to a successful QI projection (Quotes 27 and 28). Another interviewee referred to the do good of having "sensible, cogitating conversations" about what happens in your workplace (Interview no.seven, nurse).

In the meetings observed of all four teams, there was articulate evidence of common respect amongst participants. In all instances, it was noted that leaders facilitated meetings that were characterized by openness and an encouragement for "brutal honesty" equally ane leader described it. Although it was apparent in most meetings that participant involvement in proceedings was not uniformly equal, contributions were, yet, sought from all those in attendance.

The important role of the leader in setting the tone for the coming together was observed. At 1 meeting, for example, the leader stressed the importance of having "trust in the process" and gave clear guidance throughout proceedings, oft clarifying problems. It was too noted that he intentionally voted final on the contributing factors to the problem being investigated, and so as not to influence others. On another occasion, in a different projection grouping, one of the participants frequently expressed potential solutions throughout discussions equally problems arose. Respectfully, she was reminded of the need to not "jump ahead".

The benefits of undertaking the CIP, in terms of personal evolution, were raised past a couple of interviewees. One senior clinician stated that he encourages participation in the CIP "because it's good for your ain personal growth and at the end of the twenty-four hours, y'all're happy that you lot accept done something for the infirmary and for your patient and to society" (Interview no.12, medico).

The relationship betwixt quality improvement and culture

Some interviewees presented the view that the methodology and the project acted as a conduit to cultural change, rather than a practiced rubber culture being a pre-requisite for QI. They felt that this way of thinking may and so become the civilisation and a way of working (Quotes 29–31). Using the methodology and improving care can be a re-invigorating experience for staff, again providing positive cultural impacts (Quote 32). I senior nurse described the benefits she had gained in terms of her self-assurance in tackling a large and complicated problem (Quote 33). Another expressed how the CIP had developed his skills at working in a team, which over again contributes to a positive culture (Quote 34).

Barriers to successful implementation at project level

The high-level barriers to success at the QI project level included gaining support from senior and clinical staff, change fatigue, professional person rivalries, the difficulty of tackling large and circuitous problems, and contractual issues with other organisations. However, the overwhelming barrier to the successful implementation of the CIP was time and logistics. Virtually all interviewees commented on the challenge of maintaining busy clinical and authoritative workloads and undertaking the CIP (Quote 35). Some participants considered "modify fatigue" a bulwark (Quote 36).

Connected with the time factor were logistical challenges such as arranging meetings for what ofttimes involved a disparate group of professional person and administrative staff. Senior medical staff, it was noted, were generally considered the most difficult group to go to meetings. One interviewee voiced his frustration at this aspect of his project, citing the half dozen-week delay in getting a medical consultant and registrar together for a meeting.

Discussion

Qualitative enquiry, conducted via the interview and observational information collected in this study, tin can provide insights into the manner in which QI capacity and adequacy activities are organised institutionally and what components clinicians and executives believe are the most important factors for their success [28]. Our report of the SALHN CIP revealed a number of factors that lead to successful implementation of clinical practice improvement projects and the overall programme that facilitates or back up these. At the core these were an agreed and robust QI system, a skilled faculty to assist improvement teams, active interest of leadership and direction, and an agreement that teams matter. We too constitute that the relationship between a strong safe culture is not necessarily a pre-requisite for QI gains to exist made; indeed, they appear to be reciprocal, and our results testify how QI tin contribute to a strong safety civilisation. For most participants in the CIP, the time commitment for projects was meaning and, at times, maintaining momentum was a challenge. The task of combining busy clinical and administrative workloads, whilst simultaneously undertaking fourth dimension consuming projects, was invariably difficult, as were identifiable logistical challenges, such every bit arranging meetings.

The CIP has been sustained for 15 years at the level of the Department of Surgery and Perioperative Medicine and was and so scaled up across the whole of health service in 2018. At the level of the Department of Surgery and Perioperative Medicine, sustainability was promoted by clear buying of the Program, having been initially adapted from a number of frameworks [10,11,12,thirteen,14] to conform local demand [29, 30]. The Programme was strongly supported by the Head of Surgery who provided steer and momentum, had a defended resources of the Improvement Kinesthesia to support the Program, and was integrated into core business and priorities [29]. Benefits of undertaking the CIP training and projects were articulate to those who participated, in terms of improved teamwork, more than effective multi-disciplinary relationships and improvement in the delivery of quality care to patients. These characteristics were also important for successful calibration up from the Department of Surgery and Perioperative Medicine to the whole of SALHN. Additionally, the CIP had key features of interventions likely to be scaled up. The Program was based on locally generated show of programmatic effectiveness and feasibility [29]. What had been demonstrated over 15 years at the Department of Surgery and Perioperative Medicine was that the CIP was a "scalable unit" [9] that could be adopted more than widely across SALHN. CIP was associated with respected and credible senior people within the organisation [29, thirty], its impacts were observable to participants [29, thirty], and the CIP was highly relevant to gimmicky healthcare practise and organisation [29, 30]. CIP was compatible or congruent with SALHN's values and norms because it was developed internally [30]. The leadership of SALHN strongly aligned the outcomes of CIP with their own priorities of running a big wellness service in an era of rising demand and an ageing population. Their strong advocacy of the program was a central cistron in its successful adoption across the health service [31]. Their willingness to invest in the Comeback Faculty every bit a key strategic and on-the-ground resources and the Kinesthesia'southward willingness to augment its membership by mentoring others was also fundamental.

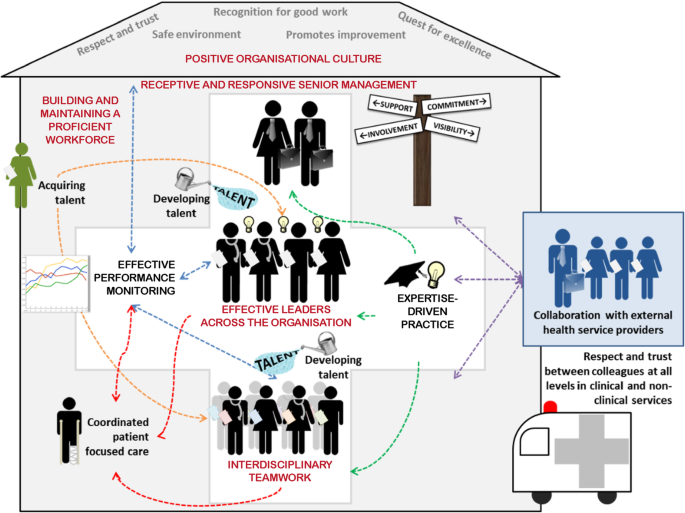

Our findings align well with our earlier systematic review on the features of high performing hospitals, i.e., those which consistently attain excellence across multiple measures of performance, and multiple departments (Fig. 1, [32]). Five of the vii characteristics of high performing hospitals were receptive and responsive senior direction, effective leaders across the arrangement, positive organisational civilisation, interdisciplinary teamwork, and building and maintaining a practiced workforce – these all featured to some degree in the CIP (Fig. i, red font). The systematic review constitute that receptive and responsive senior management and effective leaders across the arrangement involved deep interactions with staff, a hands-on style, and a proactive and continuous participation with comeback activities [32]. In our written report, senior management, who supported staff to enhance performance were active and highly visible, were like shooting fish in a barrel to speak to and actively made themselves available to collaborate and to jointly solve issues with staff. The relative ease of access to higher levels of management has been a further benefit of the CIP, facilitating a more efficient pathway to problem resolution. Under the auspices of the CIP, staff have found value in these improved advice channels, obviating the bureaucratic processes that are feature of so many large institutions. Conversely, feeding up information from the grassroots level has given senior management insight into problems to which they were previously unaware.

Components of high-performing hospitals [32] and ingredients necessary for a successful quality improvement program highlighted in red ovals [Adjusted past permission from Springer Nature Client Service Centre GmbH: Springer Nature, BMC Health Services Research. (High performing hospitals: a qualitative systematic review of associated factors and applied strategies for improvement. Taylor Due north, Clay-Williams R, Hogden E, Braithwaite J, Groene O.) COPYRIGHT 2015]

Qualitative systematic review evidence suggests respect and trust were key characteristics of a positive civilization within high performing hospitals, manifesting in staff feeling safe to speak out, take risks and suggest ideas for improvement [32]. Interdisciplinary teamwork was characterised by stiff coordination amongst disciplines and departments working together over time to achieve common goals [32]. In our study, the capacity to work in a team was a fundamental component of the various QI projects undertaken in the CIP. Having the right mix of skills and people in the room was of import, particularly for the first coming together where the "tone" was set. Most participants enjoyed the experience of team activities, valuing both the camaraderie that adult and the benefits of forming relationships with staff that normally they would not engage with in an in-depth style in the workplace.

In 2019, the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland's Health Foundation reviewed the characteristics of loftier performing National Health Service Trusts in England [3]. These Trusts were rated as outstanding past the regulator, the Care Quality Committee (CQC). Most of these take implemented an organization-wide QI program, which the CQC noted in its 2017 Country of Care report [33]. The CQC also emphasised that organisations with a 'mature QI arroyo' take prioritised comeback at the level of their board, adult and implemented a plan for edifice improvement skills at all levels of the organization, and developed structures to oversee QI piece of work and ensure it is aligned with the arrangement's strategic objectives [34]. The piece of work that SALHN has undertaken with its CIP mirrors these approaches with a strategy of buy-in, visible support from executive members, and creating a faculty to support QI teams. Persisting for 15 years seems to exist a farther ingredient for building capacity at SALHN with the highly regarded Jönköping Land in Sweden reporting like longevity [5].

The onsite CIP Kinesthesia are critical facilitators to the success of the Plan. The support of the Faculty through the provision of training, practical advice and mentorship to project teams has been an of import element in maintaining the momentum of piece of work being undertaken. In other studies of QI programs, it has been reported that having dedicated project leadership teams was by far the most commonly reported facilitating factor for the implementation of QI projects [35].

The relationship between safety culture and operation in healthcare is never likely to exist simple and is far more likely to be complex and contingent [36]. Some of the QI project team members interviewed expressed the view that undertaking a QI project is a significant correspondent to changing culture in the clinical micro-system. Working as a team with a common goal that is recognised and agreed to be a problem, with staff who do non commonly closely engage with each other in a structured way, enabled hierarchies to be flattened, and having staff generate and own the issues and solutions contributed to the perception of civilisation change – and the likelihood of it existence realised. It is possible that a goad for culture modify was a collective declaration past team members that there is a trouble that effects the quality of care provided to patients or staff well-being that is worthy of solving [37]; that they acknowledge that systems within their command may be contributing to the problem; and they were willing to use discretionary effort to work towards solving it. The process orientated tools may allow all opinions in the room to contribute more-or-less equally, encouraging authority gradients to flatten, and for causes of issues to exist generated by clinical staff who work in the area [38]. This ways that they are less inclined to experience every bit if the solution has been imposed upon them [39]. The strong overt support of the Program from SALHN executives and managers was likely to enhance the culture modify generated from QI activities [40]. The alignment of both local prophylactic culture at the level of QI teams and leadership at the level of the organisation is 1 of the three principles of the 20 twelvemonth QI journeying at Jönköping County in Sweden whereby improvement is best construed every bit both bottom-up and summit-downwardly [41].

Every bit to weaknesses, the study was a focused, deep-dive into one health system, and may not exist generalisable. A strength was to use two complementary data sources – staff interviews and observations. The observations provided validation to the interview responses and themes that were iteratively developed. The interviews were broadly representative beyond the iii CIPs and professions, including medical staff.

Conclusion

Our written report revealed interacting components that were deemed necessary for a successful QI program. These include an active involvement of leadership and management, a skilled kinesthesia to aid teams, an agreed and robust QI system, and an understanding that teams matter. Other healthcare systems may wish to consider embedding these components into their quality improvement capability and capacity building strategy. The time commitment for staff to undertake projects was meaning which can impact on maintaining momentum. These findings align well with the contemporary literature on capability and capacity building of QI knowledge and skills.

Availability of data and materials

The interview questions are outlined in Additional file three; the template for observations are shown in Additional file five. The interview transcripts are non bachelor due to ethics requirements and potential to identify participants.

Abbreviations

- CIP:

-

Continuous Comeback Program

- CQC:

-

Care Quality Committee

- PDSA:

-

Plan Do Written report Act

- QI:

-

Quality Improvement

- SALHN:

-

Southern Adelaide Local Health Network

References

-

Braithwaite J. Changing how we recall almost healthcare comeback. BMJ. 2018;361:k2014.

-

Mery One thousand, Dobrow MJ, Baker GR, Im J, Brown A. Evaluating investment in quality improvement capacity edifice: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;vii(ii):e012431. https://doi.org/x.1136/bmjopen-2016-012431.

-

Jones B, Horton T, Warburton W. The improvement journey: why organization-wide comeback in health care matters, and how to go started. London: The Health Foundation; 2019.

-

Kringos DS, Sunol R, Wagner C, Mannion R, Michel P, Klazinga NS, et al. The influence of context on the effectiveness of hospital quality improvement strategies: a review of systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):277. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0906-0.

-

Staines A, Thor J, Robert G. Sustaining improvement? The 20-year Jönköping quality improvement program revisited. Qual Manag Health Care. 2015;24(1):21–37. https://doi.org/ten.1097/QMH.0000000000000048.

-

Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Quality comeback – training for meliorate outcomes. London: AMRC; 2016.

-

Dixon-Forest M, Martin GP. Does quality comeback improve quality? Hereafter Hosp J. 2016;iii(3):191–iv. https://doi.org/x.7861/futurehosp.3-3-191.

-

Norton We, McCannon CJ, Schall MW, Mittman BS. A stakeholder-driven calendar for advancing the science and exercise of scale-upwards and spread in wellness. Implement Sci. 2012;7(one):118. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-118.

-

Barker PM, Reid A, Schall MW. A framework for scaling up health interventions: lessons from large-scale improvement initiatives in Africa. Implement Sci. 2016;eleven(1):12.

-

Goitein L, James B. Standardized best practices and individual arts and crafts-based medicine: a conversation about quality. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(vi):835–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1641.

-

James BC, Savitz LA. How Intermountain Trimmed Health Care Costs Through Robust Quality Comeback Efforts. Health Affairs; 2011. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0358.

-

Roos D, Womack J, Jones D. The machine that changed the world : the story of lean production: Harper perennial; 1991.

-

Langley One thousand, Nolan TW, Provost LP, Nolan KM, Norman CL. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance: Jossey-bass; 1996.

-

Ben-Tovim DI. Process redesign for health care using lean thinking: a guide for improving patient flow and the quality and safety of care. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2017.

-

Southern Adelaide Local Health Network. SALHN continuous improvement framework. Adelaide: SA Wellness; 2019.

-

Ziegenfuss JT Jr, McKenna CK. Ten tools of continuous quality comeback: a review and case example of infirmary discharge. Am J Med Qual. 1995;10(4):213–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885713X9501000408.

-

O'Neill NE, Baker J, Ward R, Johnson C, Taggart Fifty, Sholzberg M. The development of a quality improvement projection to better infection prevention and management in patients with asplenia or hyposplenia. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9(three):e000770. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000770.

-

Louie JP, Alfano J, Nguyen-Tran T, Nguyen-Tran H, Shanley R, Holm T, et al. Reduction of paediatric head CT utilisation at a rural full general hospital emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:912.

-

Braithwaite J, Clay-Williams R, Taylor Northward, Ting HP, Winata T, Hogden E, et al. Deepening our Understanding of Quality in Australia (DUQuA): An overview of a nation-broad, multi-level analysis of relationships between quality management systems and patient factors in 32 hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;32(Supplement_1):8–21.

-

Wagner C, Groene O, Thompson CA, Dersarkissian Chiliad, Klazinga NS, Arah OA, et al. DUQuE quality direction measures: associations between quality management at hospital and pathway levels. Int J Qual Health Intendance. 2014;26 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):66–73.

-

Benning A, Ghaleb K, Suokas A, Dixon-Woods One thousand, Dawson J, Hairdresser North, et al. Big scale organisational intervention to improve patient safety in four U.k. hospitals: mixed method evaluation. BMJ. 2011;342(feb03 one):d195. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d195.

-

Bevan H. How tin we build skills to transform the healthcare organisation? J Res Nurs. 2010;15(two):139–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987109357812.

-

Jones B, Vaux E, Olsson-Brownish A. How to get started in quality improvement. BMJ. 2019;364:k5408.

-

Atkinson South, Ingham J, Cheshire Yard, Went Due south. Defining quality and quality improvement. Clin Med (London, England). 2010;10(half dozen):537–9.

-

Strudwick RM. Ethnographic enquiry in healthcare – patients and service users as participants. Disabil Rehabil. 2020:one–five. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1741695.

-

NHS England. Skilful governance outcomes for CCGs: A meeting observation guide to support evolution and improvement of CCGs. London, U.K. Contract No.: Gateway reference number 03855.

-

Braun B, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(ii):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

-

Dixon-Woods M. How to improve healthcare improvement-an essay by Mary Dixon-Woods. BMJ. 2019;367:l5514–l.

-

World Health Organisation. Practical guidance for scaling up health service innovations. Geneva: WHO; 2009.

-

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. New York: The Free Press, MacMillan Publishing Co; 1995.

-

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629. https://doi.org/x.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x.

-

Taylor N, Clay-Williams R, Hogden E, Braithwaite J, Groene O. Loftier performing hospitals: a qualitative systematic review of associated factors and applied strategies for comeback. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;fifteen(ane):244. https://doi.org/x.1186/s12913-015-0879-z.

-

Care Quality Commission. The State of Health Care and Adult Social Care in England r2016/17. London: CQC; 2017.

-

Care Quality Commission. Cursory Guide: Assessing Quality Improvement in a Healthcare Provider. London: CQC; 2018.

-

Robert G, Morrow E, Maben J, Griffiths P, Callard L. The adoption, local implementation and assimilation into routine nursing practice of a national quality improvement programme: the productive Ward in England. J Clin Nurs. 2011;twenty(7–8):1196–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03480.10.

-

Scott T, Mannion R, Marshall M, Davies H. Does organisational culture influence health intendance performance? A review of the evidence. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8(two):105–17. https://doi.org/x.1258/135581903321466085.

-

Dixon-Woods Thou, McNicol Southward, Martin G. Ten challenges in improving quality in healthcare: lessons from the Wellness Foundation's programme evaluations and relevant literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(x):876–84. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000760.

-

Fitzsimons J. Quality & Safety in the time of coronavirus-blueprint better, learn faster. Int J Qual Wellness Care. 2021;33(ane):mzaa051. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa051.

-

Vaughn VM, Saint South, Krein SL, Forman JH, Meddings J, Ameling J, et al. Characteristics of healthcare organisations struggling to improve quality: results from a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(one):74–84. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007573.

-

Sutcliffe KM, Paine Fifty, Pronovost PJ. Re-examining high reliability: actively organising for safe. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(3):248–51. https://doi.org/ten.1136/bmjqs-2015-004698.

-

Bodenheimer T, Bojestig M, Henriks G. Making systemwide improvements in wellness care: lessons from Jönköping County, Sweden. Qual Manag Health Care. 2007;16(1):10–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00019514-200701000-00003.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros would like to give thanks all the participants who agreed to be interviewed. Special thanks to Beryl Sutton for organising interviews with participants.

Funding

The research was funded via a contract between SALHN and Macquarie University. The funder and the researcher collaboratively developed the research aims. The funder had no role in the selection of the participants, data drove, data analysis or conclusions.

Author data

Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived by PH, JB, and RP. The research proposal, ethics and site-specific approving applications were written past PH and LW, and reviewed past JB, RP, and RCW. Interview frameworks were developed by PH, RCW, LW, and MB and reviewed and revised by JB and RP. Interviews, focus groups, and observations were conducted and analysed by PH and MB. The first draft of the paper was written by PH and reviewed and revised past the residuum of the study team. The writer(due south) read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Requisite ethics and governance approvals were obtained earlier inquiry commenced – SALHN Man Research and Ethics Committee: HREC/eighteen/SAC/369 and Office for Enquiry: SSA/xix/SAC/162. Written informed consent was obtained from study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

PH runs training in quality comeback for the Australian Quango on Healthcare Standards. RP is the Managing director at SALHN responsible for the Continuous Improvement Program.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilize, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as yous give advisable credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other tertiary political party textile in this article are included in the commodity's Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted utilise, y'all will need to obtain permission direct from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nil/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this commodity

Cite this article

Hibbert, P.D., Basedow, M., Braithwaite, J. et al. How to sustainably build capacity in quality improvement inside a healthcare organisation: a deep-dive, focused qualitative analysis. BMC Wellness Serv Res 21, 588 (2021). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12913-021-06598-8

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06598-8

Keywords

- Quality improvement

- Quality of wellness intendance

- Qualitative research

- Patient safety

Source: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-021-06598-8

0 Response to "what resources are needed to develop improvement capability in hospitals"

Postar um comentário